South Africa –

Celebrated Photographer Roger Ballen has been photographing for around 50 years mostly in Johannesburg, South Africa. His work is prominent in its dense and visceral images of real and imagined situations, treading a thin line between the dream and the nightmare, drawing the viewer in and then taking them along an existential journey. He has spent most of his life documenting the social, economic and cultural impoverishments faced by his subjects, in a bold and experimental manner, taking us into the dark recesses of their minds, and in turn revealing to us our own dark sides.

Manik: So, I’ve tried to focus the whole interview on your recent book ‘Asylum of the Birds’ and the movie primarily, because much of your personal information has already been revealed in previous interviews.

Roger:Yeah, that’s fine. Let’s concentrate on the film, that’s great.

Manik: You use the iconic symbol of the birds and then you juxtapose it with the mysterious dark underworld of your imagination. What is the purpose of creating this paradox?

Roger:Well. I think it’s a matter of creating a metaphor, I think good art’s about metaphors. It’s about showing visual relationships that subconsciously you’re aware of. I think the purpose is actually to create allegories, to create metaphors, to create new meanings through the relationship of the birds, which in a way is a symbol of peering into this dark, sort of a dark underworld.

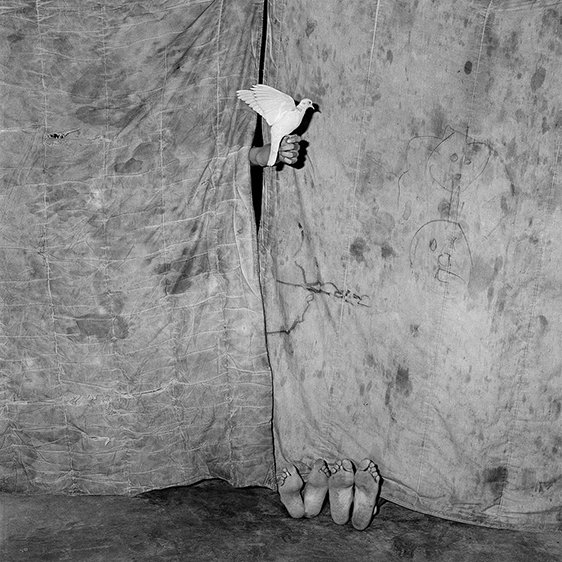

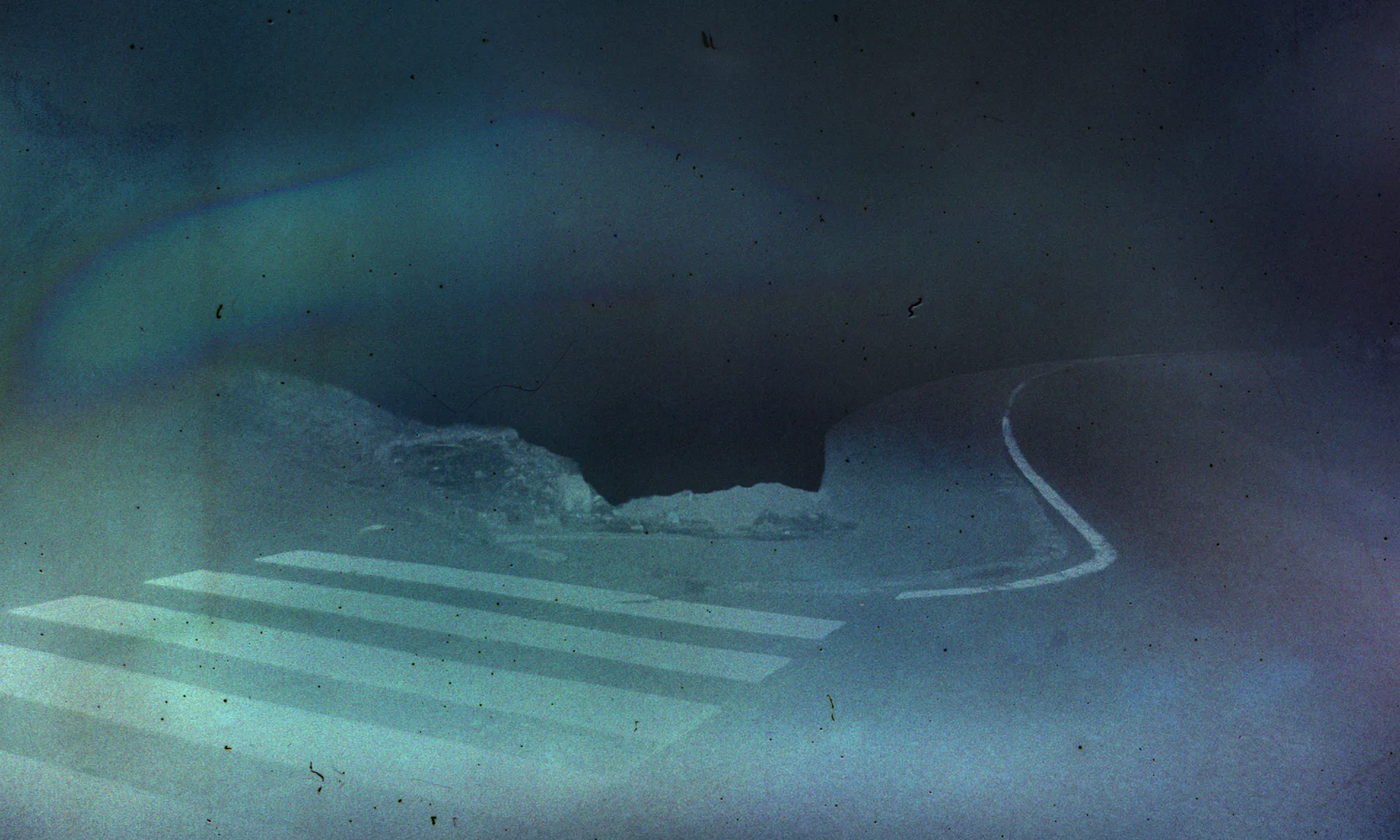

Take off, 2012

Take off, 2012

Manik: You’ve been very open about your intent in choosing titles for your books and projects. How did the title ‘Asylum of the Birds’ originate?

Roger: Well it’s—I’m just trying to remember actually how the word asylum came about. I think it came about because in the English language ‘Asylum’ has two meanings. One is place of refuge. And so the place where I work was a place of refuge for a lot of people. And secondly it’s a place of madness. So I thought the two meanings of the word enable language, in so many ways, to describe the place that I worked in. And then the place that I worked in, with little birds, I decided in 2008 to work on the series concentrated on birds and the relationships to the so-called asylum of the bird’s house.

Manik: Was it always going to bear this title or was it created after you made the work?

Roger:No. I think The Asylum, Asylum….. It’s a good question. You know, I’m just trying to remember. The title I thought about quite early in the project. I think it was full of—you know, probably in 2009 I had already decided that Asylum was the right title.

Manik: And you started this work six years back, am I correct?

Roger: I started—yeah, I started working on the project in earnest in the middle of 2008.

Manik: Ok

Roger: It took me… it took me a little over five years

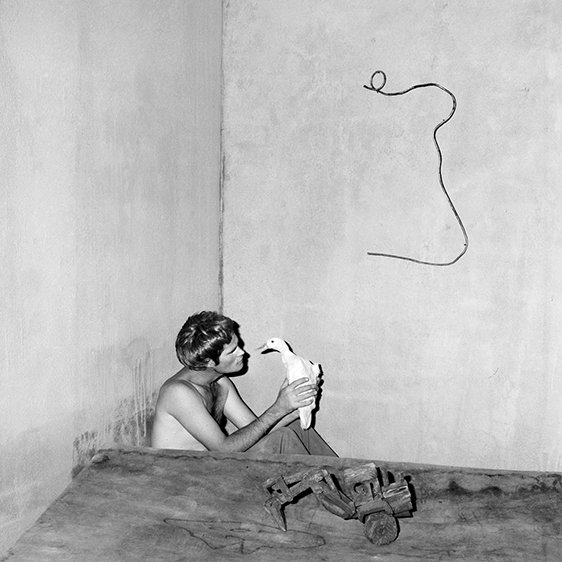

Ambience, 2006

Ambience, 2006

Manik: Ok. In any case, the title came a bit later, after the project started.

Roger: Not really much later. I can’t really remember. It was very, very close to when I began. All my projects that I’ve been involved in, for all these years, usually start with a title. Whether it was ‘Boarding House’, or whether it was ‘Shadow Chamber’, in a way I sort of come up with a word and I try to define it. So, I think, that although I can’t be 100% accurate, the title came quite early on in this project.

Manik: Speaking of comparing your previous work, in ‘Asylum of the Birds’ you use people in a more subtle way, by just suggesting their presence—like with their hands, or parts of their face. You’ve fore fronted the use of props, scenery and birds specifically for this project and your book. So if I may ask—why?

Roger: Well, you know, for many years—I guess up to about 2003—I used portraiture quite frequently in my pictures in one way or another. And then I… I started to feel, I think, that the subjects, the faces of the subjects, were dominating anything else in the picture, no matter what else was in the picture. The people would view the picture, they would just keep coming back to the subject, you know, the poor, the rich, are they funny, are they this, are they that. And never looked at the other things in the picture, you know, the, really, really important. So I started to feel that I wanted to get away from this. I wanted to make more abstract statements and, get away from the personalities of the people in the pictures. So beginning in about 2003 I started to gradually remove the people.

Manik: And for this project, was it more of an intentional effort, or was it quite natural?

Roger: Well, it’s never— it’s never— I don’t really— when I take pictures, I don’t really have any ideas. I don’t really think, ‘what am I going to do? what am I going to take?, you know, I just do the work. And so it’s a process that takes time, and takes evolution and, you know, builds on itself basically. So it’s a great producer, it gives you other things. So it’s very much a dynamic process, rather than one that is dominated by what I want to do from the very beginning. It evolves at its own speed, in it’s own right and it’s own way and I can’t… I have no way of predicting where the picture, where the product, will end up.

And anyway, that’s the challenge of what I do, that’s why it’s a creative process. It’s not something I just conceptualize and then do, you know. It should challenge me, and it should surprise me. Otherwise there’s no point for me to take these pictures.

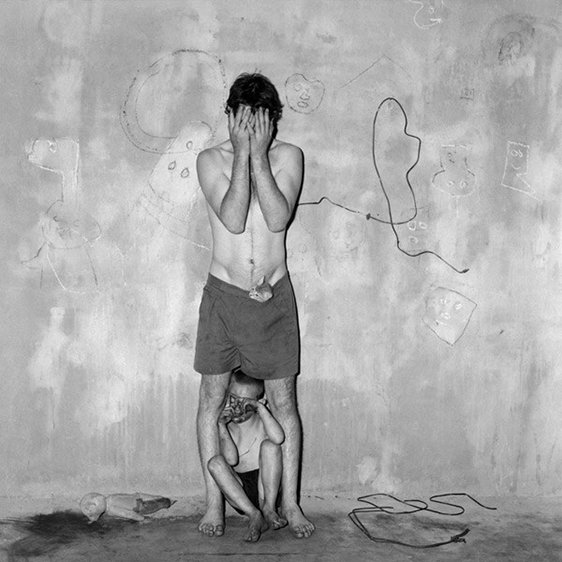

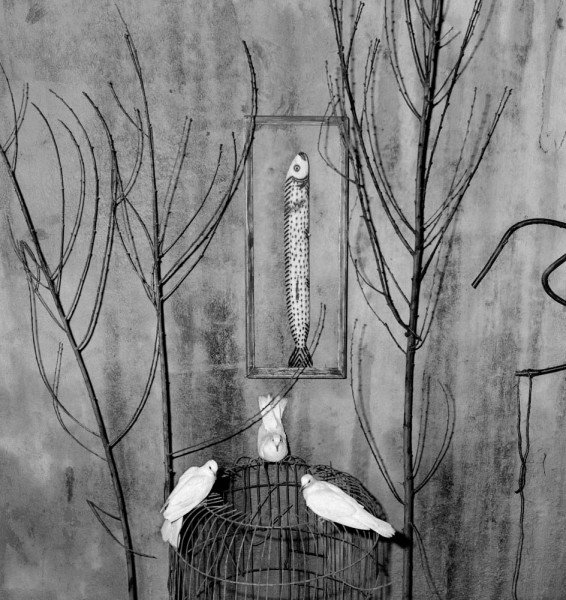

Blinded, 2005

Blinded, 2005

Manik: So tell me one thing: Why are the drawings so essential to this work? Are they a representation of people outside this world that you create, or do you have any other reason for it?

Roger: Yeah. The drawings add another layer to the work, you know. I think the drawings play a very important role in my photography. To try to really come to grasp what the meaning of the drawing is, it’s not so easy, because sometimes the drawings are very formalistically made, and other times they are very specific to the place itself. The drawings sometimes are mine and sometimes they’re not mine. They’re sometimes there before I start, sometimes I add some style to them. And sometimes the people I’m working with also do them. So it’s really hard to actually pinpoint what the overall meaning of the drawing actually is. Each picture, that relationship changes somewhat. But one could say, I think, that the drawings are, one way or another, do represent the world as spirits. And I think, you know, when people ask me what influence living in Africa has on your life, I think maybe that’s one of the influences, because people here are very much influenced by the spirit world.

Manik: And do you relate yourself to it?

Roger: Yeah. Well, here, I don’t think anybody can ever deny it.

Manik: Which clearly means that you’ve had your experiences…

Roger: Yeah—I mean—yeah, you know. I think it’s, yeah. I have experiences all the time.

Manik: Would you like to share something?

Roger: It doesn’t have to be, like, somebody walks into your life, obviously. But you know, there are a lot of strange, unknown, ambiguous aspects of our condition, human condition,and probably anybody’s condition on the planet. So, you know, there are a lot of things we don’t understand. So, you know, I think that’s one of them.

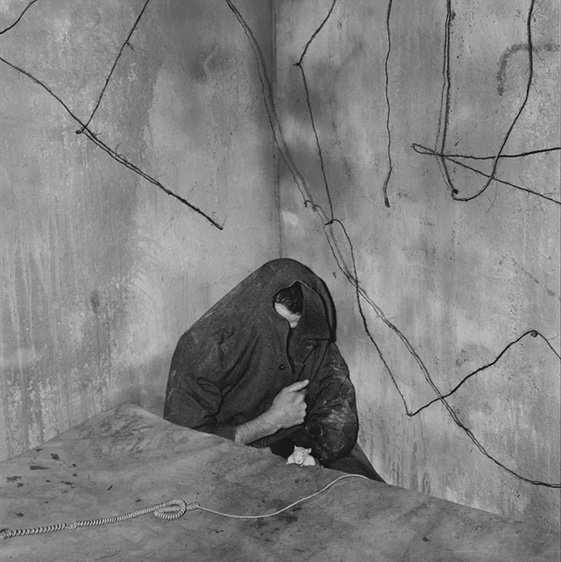

Transformation, 2004

Transformation, 2004

Manik: Would you like to share one of your personal experiences?

Roger: I don’t really have anything personal like I woke up one morning and saw somebody following me. But it’s just that, you know, we can’t really, really put our finger on these things. And I think, you know, you being in India, you know, this type of philosophy, especially in the Hindu philosophy, it’s very prominent, it’s a very prominent…

But the Christian religion or the Jewish religion is not so. I think you are one of the few people that has actually brought this up in any real way, and it’s quite interesting that you—because the people grow up in the western world, Europe or the United States, really. The satisfaction of their condition is really repressed, it’s not part of the puzzle, the culture is very rational, scientific, and not very emotional, I guess emotional is a bit. Not very. The people are told very early, from childhood, not to believe in these things, that they’re just fantasy and they shouldn’t pay any attention to it. So people grow up trying to not be in contact with any other condition, and also not trying to seek it out. Whereas in a culture like India it’s absolutely prominent…

Manik: So it has influenced you and your work in some way?

Roger: Yeah it definitely has. I mean, that’s the thing, you know—the untouchable, the invisible. I mean once you try—at least, what I’m trying to do, is trying to make the invisible visible. Well, it’s mysterious to me, trying to make them a little more concrete, a little bit more evident. So, yeah, photography helps me explain parts of my psyche, parts of my experience, helps me concretize these in some way. So, you know, it’s all sorts of parts of myself there. And that I wasn’t really aware of and you’ve woken up parts of yourself that you weren’t even aware of. It’s a very gratifying experience.

Encaged, 2012

Encaged, 2012

Manik: You’ve stated previously, ‘When I create photographs, I often travel deep into my interiors. A place where dreams and many of my photographs originate. I see my photos as mirrors, reflectors, and connectors that challenge the mind.’ How would you define that whole process?

Roger: Well, it’s really difficult to define the process, because it’s so interactive and it’s so, interactive between me and the place. It’s interactive by different levels of my mind. You know, how was my work even able to tell, how it even talks how I’m talking now. It’s very mysterious, and it’s not really something you can really put your finger on. I mean, how do I, how am I able to say what I’m saying now, how is this happening, too? You know, the way that we are, the way that we… You’ve really got to understand most things about our own identities; we don’t understand how we work. So, I mean, the photographs, the purpose of taking the photographs for me, is to try to better assist me to get to different places in my mind that I’ve been unaware of. Reveal things about my presence.

I’m not saying that I can… there’s no end point to this, you know, I always say if there was an end point then I would give up photography. So there is no end point, but it is a process of learning, it is a process of revelation. It’s also a process of, you know, I think I’m really, I guess I’m privileged in a way that I’m involved in it. I am able to use photography in this way. Most people in photography are just documenting what’s out there, you know—taking a picture of a sunset, take a picture of the Taj Mahal, take a picture of a grandmother. They don’t really use the camera to get deep inside themselves to reveal things about themselves that they really aren’t very aware of in any other way. So I think I’m really quite privileged, in a way, I’m really taking pictures of my interior. These are shots from the subconscious, of the subconscious.

I mean, if somebody said to you, sometimes when I give classes I say to the class, ‘Close your eyes, close your eyes. Turn your eyeballs around and photograph what you see.’ So that’s what I’m doing.

It’s a complicated process, you know, it’s not something I can just say, ‘Oh I go into a place…’ and this, that and the other. Every time it comes in a different way, and it’s a very psychologically interactive process between myself and myself. And between myself and the people, myself and the place, and between myself and the animals.

Manik: And that has been your experience only for this project or for all your projects up to now in your photographic career?

Roger: The pictures become more and more psychological and more and more complex, and more introspective. So, this has been the traveling of the pictures for the last twenty years. My earlier work, which you can see on my website, but when I did ‘Boyhood’, when I did this overlaying trick at the beginning, it was the first time I was in India. I was in India for about six months, and you see the purpose of the work was to discover my own boy through other boys; I was trying to find my own childhood. So in a way, this also was a psychological journey. But the images certainly weren’t as complex as they are today.

Manik: The subjects you photograph, and the environment, these lead to your artistic vision? Or are you inspired by this, you know, this conscience mind of yours?

Roger: Well, I’m not really—I don’t really believe so much in inspiration. I really believe in hard work, focus, dedication, passion, and commitment. I think those are the things that made my photographs over the years—just a lot of, you know—totally dedicated to taking these pictures all these years, and actually passion about it and, I think, really that’s been the reason behind what I do. You know, for me it’s been a psychological journey; it’s like somebody’s writing a diary. In each picture I’m writing a diary of myself at that time, that’s what I believe in.

Bewitched, 2012

Bewitched, 2012

Manik: And how would you define your artistic vision?

Roger: I think it’s— I think there are a couple of ways, if it’s psychological, or it could be called theatre of the observed. Or it could be called dark humor. I think those are probably good words; dark humor; theatre of the observed; journey into the interior. You know, it’s fundamentally psychological statements through visual media, which is photography.

Manik: The short film shows you working on the project, but it also interjects clips that are quite ambiguous. Is it always important for you to create work that keeps the viewer guessing?

Roger: Yeah, I think that’s where something becomes art. You see, I think if the pictures challenge people they shouldn’t give people the answers; they should make people think, raise questions for people. So it really is important that the work provokes people, makes them think, prods them. It shouldn’t give them reality on a spoon, it shouldn’t be spoon-fed to them, it should challenge them. I think if the work has an aspect, I should say, it’s very important that the work has that aspect for me, just for me alone. The pictures have to challenge me; if the pictures don’t challenge me then there’s no point in taking them. I’ve always said that the best pictures for me are always the ones that I don’t understand. It doesn’t mean that these are all good pictures, I mean—it has to be a fundamentally strong, powerful, intense photograph. Sometimes people say I can’t talk about it, I don’t understand it. Yeah, but if you don’t understand it you can’t talk about it because there’s nothing to say. We see that a lot in art. But for me it’s pictures that have intensity, and an ambiguity and strength and a power to them—challenges my subconscious. Those can be the most important images; those are the ones that beat me to my next creations and challenge me to go onwards.

Manik: Do you get this a lot from your audience—that they are not able to relate to the intensity of your photographs? Do you hear this often?

Roger: Yeah. Most people say they see the work as dark. You know, when they say that they’re relating to it, so it’s really challenging the viewer. When they say it’s dark it’s because they’re scared of themselves basically. So they don’t know what to do, they said they call it dark but usually it’s a picture made in their mind. But they’re scared of coming into contact with their own identity, so they try to label it, they try to blame me for something. Or try to say they can’t understand it. But if somebody said something like that, or if it’s dark, it usually means that the picture has had an impact on them already. So yeah, I think very few people who see my photographs forget, and that’s very important to me that, them saying things that, whether people like it or not, my pictures have impacted people. Which is great! That’s what you want as an artist, you want people to walk away and remember what you do.

Serpent Lady, 2009

Serpent Lady, 2009

Manik: The dark depiction of these environments—does it reflect your opinion of these places?

Roger: See I don’t see—you might call it dark, but I don’t see that dark; that’s the difference. I don’t see that it’s dark. Some of the funniest moments in my life are when I take the pictures. Some of my best friends—I guess my best friends in South Africa—almost, nearly all of them, are from these places. So, I enjoy being there, I love being there, I’m passionate about being there. I really love a lot of the people I work with and have a really long-term relationship with. So, I don’t see this dark, I don’t see this dark.

Manik: So is there something more positive you want to show as well? Your film ends with the line, ‘The light comes from the dark’.

Roger: Yeah, well I think that’s what I want to say. I think the positive thing is when you deal with the unknown aspects of yourself, the parts of yourself that you haven’t been able to come into contact with, that you’ve repressed or that you’re scared of. If my pictures can help you, or assist you in this process, then that’s really positive, that’s really positive. That you actually can edit you fears out, and by editing your fears out you can find out you’re a better person. So, yeah, that’s what I’m doing. I can’t guarantee anything, and I don’t know what one person thinks, and what another person thinks, or whether what somebody says is actually what they feel. But that’s my hope. I think it does manifest itself on a part of your conscience.

Manik: You have also said, ‘It sticks in the mind; it doesn’t get out of the mind, and is turned over and comes in all sorts of ways. And it actually extends the consciousness of the person’, and that is your purpose of photographing, right?

Roger: Well, I would say there are two purposes, really, because of my own purpose, which I take pictures for—you know, I can’t take pictures for other people. If I’m not challenged myself then I will never be a good artist. I think that’s the trouble with a lot of art these days is that artists are trying to make pictures, paintings, or photographs, for the public rather than from something inside. They’re trying to figure out basically what people are buying, what they like. That’s never been the purpose of me taking the pictures. It’s always, as I said, been a way of writing my own diary. But so, for me, it should be a challenge and I would hope the pictures would also be a challenge for other people. If they’re a challenge for me and they are a challenge to other people; if they contribute to my understanding of myself, and contribute to other people’s understanding of themselves, well that’s great, I’ve achieved everything I wanted in those pictures.

Caged, 2011

Caged, 2011

Manik: What is it about the subconscious mind that really fascinates you?

Roger: Everything. Just everything.

The subconscious mind is a product of the planet’s evolution. It’s a product of the universe. The subconscious mind is—it starts from the beginning of, I guess, life on this planet. So in a way it incorporates all the aspects of the universe of the time, so you know, it’s a vast, vast rich, unknown. It’s a vast source of personal wealth and gratification. The subconscious links us with everything else in the planet.

The subconscious really makes the— you know, the subconscious is the thing that drives human behavior. And the subconscious, you know, I don’t understand it, but…

Manik: Something personally I have been really curious about is about your imagination process. How do you pre-visualize your subject? What goes on in your mind?

Roger: I don’t plan anything.It’s almost like I have a Buddhist mentality, I go to the picture, and take the pictures with a silent mind, quiet mind. Then when I’m there I interact with the place, with my own mind, with the people, with the drawing, and with the animals. And nothing is— I don’t use words, I don’t walk in and say I want to create pictures that are dark; I don’t take a picture that’s certain. I don’t, you know— to makes these pictures is like a painting. If you look at a painting, it’s like a thousands brush strokes to make a painting. Well, each one of these photographs is like thousands or tens of thousands of little decisions that keep adding up. As you move all of the pictures you start creating a life around what you’re creating. Then there’s a certain point, where you feel there’s something organic that you create, there’s wholeness to what’s in front of you and then I take out the camera. Usually in photography it’s quite important that you create something that has a momentary effect. Where does photography separate itself from the other medias? It separates itself from other medias because it’s the only media that tells you that time can’t be repeated. It’s dealing with micro-moments, so I always feel it in my pictures, you know, to complete whatever I do there needs to be a micro-moment. And I feel that’s really important in photography—it’s sometimes the most difficult thing to achieve, so, you know. You work with people it’s a great foreground and background, but then it’s still not enough in photography. It might be all right in an instillation that you’re making, but it’s still not enough in photography. You’ve got to find something that transforms that whole thing in front of you through the mind. That’s very difficult; that’s part of my imagination; it’s part of my technique. It’s not something I can predict because by the very nature of the moment, it’s unpredictable, it’s unpredictable. It’s symbolic for what photography—you’ve got—photography is in a way a metaphor for the unpredictable.

Memento Mori, 2012

Memento Mori, 2012

Manik: What do you mean when you say that good photography is about making strong, complex, visual relationships?

Roger: Yeah. That’s what I think it is, I mean, for me personally, other people may think photography is about making beautiful statements, or making statements that help them memoir their life. But for me, I’m only talking about myself, because I can’t talk about— I don’t really— what other people do is their business. But for me it’s very important that the photographs are intense, complex and reveal something about our own condition in a profound way. And underlining ‘Profound way’, because most things we see aren’t very profound.

Manik: In your recent book, published by ‘Thames and Hudson‘, you have written this small paragraph: ‘In “Asylum of the Birds” I have photographed birds interacting in a space characterized by discarded objects, other animals, ghost-like drawings that could have originated in the care of being part of funeral ceremonies’. What do you mean, ‘ghost-like drawings’? Why are your references on the dark side, or negative side?

Roger: Well, firstly, the dark isn’t the negative and the negative’s not the dark, you see?

So that’s, you know, you live in India so nobody— somebody— that’s so much of, you know— the Hindu people, they’re just going from one phase to the next. So it’s not dark if you go from one thing to the next…

Manik: Well, according to the Hindu mythology, it’s quite sacred.

Roger: Yeah. So that’s why I’m saying to you, I don’t see why people… It’s Western culture, you’re speaking like. You’re making a comment like you would very commonly find in Western culture. But for me it’s not a very negative or dark thing—it’s not negative or dark. Why is it negative or dark?

Manik: But when you say ‘ghost-like drawings’—

Roger: Yeah, but those aren’t drawings unless— like why is a ‘ghost-like drawing’ dark or negative?

Liberation, 2011

Liberation, 2011

Manik: So you would not agree to it completely?

Roger: Well I wouldn’t say, I wouldn’t say. They are ‘ghost-like drawings’, yeah, because as I said earlier, they have something to do with a sort of spirit world perhaps. Perhaps. But some of the drawings aren’t even mine. But yeah, but that doesn’t mean that just because they’re ‘ghost-like drawings’ that they’re negative or dark.

They can be just the opposite. They could be light and illuminating, and could provide revelation rather than anything else.

Manik: I might be able to relate to what you are saying. But you know, a lot of the times the viewer/audience is not able to understand your work…

Roger: Well, I think your question—as I said, I am very pleased with your questions. Most people don’t ask me these questions, and I was just telling my assistant today: I said, ‘You know, most people ask me the same questions: “what do people think about your pictures? which camera did you use?”’ You know, they ask me the same sorts of questions, they don’t go very far. They never asked about the drawing, you know, the drawings are central to my photography for the last fifteen to twenty years, they don’t even understand what the drawings are about, they have no understanding. They don’t try to penetrate to what the purpose of the drawings are, or what the drawings mean. Or what the drawings mean to the viewer, so the comments that you’ve made are very interesting to me, and very few people actually ask these questions. And I think it’s a shame they don’t ask these questions, because the drawings in my work are things that really separate my work from a lot of other peoples’ work in photography.

My photography is an integration of drawing, sculpture, installation-making and food photography. And to not talk about the drawing in any real way is to neglect a lot of what the pictures are really about.

Manik: And in your recent project, ‘Asylum of the Birds’, every image has very interesting, fascinating, freaky drawings in the background. Which make you think. There could be so many meanings.

Roger: Yeah. Well, I think… this is exactly what people should ponder; it’s exactly what people should be pondering in the work. And they should be trying to ponder the meaning of the drawing and actually the formal qualities of these drawings, and how they relate to other things in the work. And how what I’ve done over the years is very… What contribution am I making to photography and the field of art? I think these are all important questions that a lot of people don’t actually come to grips with in any real way. I think your questions are good. I’ve probably… I know we don’t know each other very well, but I think you probably can appreciate some of these things a lot better than somebody growing up Norway, or England, or the United States. Because, as I said, the aspects of the human life have really regressed.

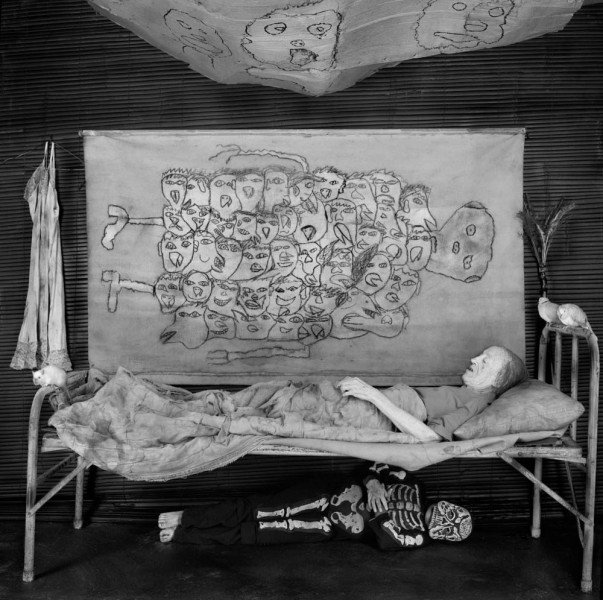

Deathbed, 2010

Deathbed, 2010

Manik: There is a celebration in Death as well.

Roger: Yep, yeah, but in Western culture death isn’t seen as a celebration.

Manik: Which clearly refers to the cultural background—understandings of artwork—and that’s a very interesting discussion. How do people refer to your work in different parts of the world?

Roger: Yeah, definitely. You know, it is difficult for me to say, because I meet so many people over the years, and I don’t always understand the language. Sometimes I meet this one and that one, but I’m hardly living in the culture, so it’s always difficult to come to any general conclusion. You know, I come to a country, I’m there for three or four days, usually I have the same questions and that’s it. I meet a few—ten, twenty, fifty people—and have an opening sometimes and thousands of people sometimes…

Manik: I know it can get really monotonous after a point.

Roger: It’s really hard for me to judge. I definitely can see there are differences. I’ve had a lot of shows in Russia; there seems to be a different— Eastern Europe, I think, there are people living their lives in a little bit more… in a less technological way perhaps.

Manik: And does it also affect you personally? I can imagine that working on every image was a long process; there are a lot of elements and layers.

Roger: No, I don’t really get involved in that too much. I’ve been doing this a long time now. I’m very confident about what I’ve been doing and I know that my work is strong. So I don’t care who you are; nobody likes criticism, you could be Einstein and you probably still wouldn’t like criticism. You’re always going to find people who find negatives in what you do. But the positives far outweigh the negatives. I’m not really too phased by comments people make here and there, you know—you really have to take the good with the bad. I think I’ve reached a point in my career where I’m not heavily affected and I don’t generally get very many negative comments. Usually, it’s been my experience in my career that, the more negative comments come from people who have the most to protect inside themselves. That’s usually their own psychological issues they’re projecting onto me; the most negative comments usually come from them, that type of personality.

Manik: One of the interesting things about your work is that it’s not just photographs; it’s a collaboration of different mediums—from sculptures, to drawings, to photography. In the past, you’ve worked with different mediums—you’ve worked with bands; you also made a small documentary. On what bases do you select these different mediums, and is there anything that you’re working on in the future?

Roger: Yeah, I mean, hopefully in my next projects I will continue to do videos, because I feel video’s is a really very important way of getting my artwork out there. The one video that I made, the music video, it got fifty million hits on this thing. So fifty million people saw what I did in some way or another. And you know, the ‘Asylum of the Birds’ video is probably getting nearly a hundred thousand on that. So it’s a really a good way of getting your work out there, plus working in other media allows you to explore different parts of yourself that are unique to that medium. So photography allows you to express yourself through photography, but you can find other things in sculpture, installation making and video, that you can’t actually do in photography. So in my exhibitions now, at least in the museum ones, I’m making installations, so people can walk in the space and it feels like the place of my photographs. In my show that I’m having in South Africa next week, I made a sculpture that feels like subjects in my work. So I’m now working, in my exhibitions now, showing my videos and making sculptures, and making installations, as well as showing my work. I think it gives people a much wider view of my aesthetic, it really does. My aesthetic now goes beyond just the photographs I take.

Manik: Do you brief your subjects on exactly what you want or where you’re using them in the photograph? And if so, do you allow them any power over their artistic decisions, or it’s completely yours?

Roger: Well sometimes they do things spontaneously, sometimes somebody just decides to do something—they think, ‘Oh, I’m going to put my hand on my mouth’, because they think that’s funny, and then they do it. And I think, ‘Wow, that really works in this picture’. It’s that spontaneity. Or I may say, ‘Put your hand on your mouth’ or they might do it spontaneously. And while they do it maybe they’re moving their leg in such a way that that’s more important than when they’re touching their mouth. So it’s a very, very complex process, you know, it’s not necessarily only what I say to the subjects; the subjects are also involved in expressing themselves in their own way. For example, one of the most important things in my pictures: the eyeballs of the subject. The eyeballs—and you can’t tell somebody, ‘Oh take your eye balls and look right, look left’, you know, you’ve got to capture that

Manik: Of course

Roger: So it’s interaction again. I can’t really say because every picture’s different. We keep going back to the people but in the last two series—‘Boarding House’ and ‘Asylum…’—80% of the pictures don’t even have any people in them; they have animals. So what about these animals? What am I doing with them? Ha. Yeah, maybe I’m a good animal trainer… (Laughs) Maybe I can speak goat, and I can speak a little chicken….

Onlookers, 2010

Onlookers, 2010

Manik: Well, you never know, you may have that secret art?

Roger: Yeah maybe. I probably can almost.

(Both Laugh)

Manik: There’s an allegation on your work: the particular subjects you target are often people on the fringes of South African society, people who are at their most vulnerable and could be easily exploited—not by all but by some. So, how do you deal with this situation when people put question marks on your photographic art and process?

Roger: You know, this issue of exploitation is as old as photography. So it’s not something new, and I’m not the first one to be accused of this. So I think at the end of the day you really have to live with yourself, and say, ‘Well, nobody in a million years knows what goes on between me and my subject’. Maybe the subjects are rich people, maybe they’re not. The people just don’t know those people. So what you’re seeing is the photograph, but it doesn’t necessarily really reveal anything about the subjects themselves. So, as I said earlier, for me it’s usually an excuse for people who… The people who scream the loudest are the ones that have the most to hide inside. That’s all I can say. And if you look everyday in India or America, or South Africa, and you look at the newspapers or looked at the T.V., and see what the CNN or the BBC or any of these other channels, or what any of these newspapers show every day—every day: day in, day out—it’s far worse than anything that I do. So you know, to me, as I just said, it’s very clear to me that the people shouting the most have the most to hide. That’s all I can say….

Manik: When you say, ‘…it’s far worse than what I do….’, do you accept that there is something wrong somewhere, or not at all?

Roger: No I don’t think, I don’t think that anything I’m doing is wrong, because I’m not hurting anybody, and I’m not. I’m actually transforming things, so what you seeing isn’t necessarily… Nobody can take the pictures like me. So what you really see is a Roger Ballen aesthetic, you know, that subject is— You know, if you spent the next thousand years with that same subject that I spent time with, you would never take the same pictures as me. Photography is no different from painting or writing. Let’s say there was a great Indian writer, and you had met somebody or were corresponding with someone in the Himalayas or wherever. And the Indian writer you went with to the Himalayas—he would write great poetry, and maybe make a novel out of it. You can’t, you wouldn’t think that you could write the same as that person. You’re seeing the same thing, but what comes out is completely different. People see photography as an objectifying—it’s not objectifying. It’s purely a subjective view of the world. So this is again what people don’t understand—that the pictures are really transformative. That whatever is out there is going to be transformed. It’s not necessarily an objectification of what’s there.

Scream, 2012

Scream, 2012

Manik: And in the process no human or animal was exploited at all?

Roger: I mean, I don’t even know what you mean by exploited.

Every human being, every human being, has its purpose. Always remember that. Don’t ever think that anybody is any better; most people aren’t any better than anybody else. We all are destroying the natural world, we’re all selfish, and we’re all egocentric. And so to use this word ‘exploitative’ is a very dangerous word, and I don’t believe that I’ve exploited people.

So I’m not really… I don’t have any… I don’t feel uneasy about the work because I have to look myself in the eye and I can sleep well about this. That’s all I can do, there’s nothing more I can do. I can argue till I’m blue in the face, that’s how I feel. You know, if you went and saw the subjects that I’ve worked with over the years, I’m talking about twenty or thirty years, I doubt you could probably find anybody that didn’t like me.

Manik: Ok

Roger: What more can I do?

Manik: You see, of course you’re doing what you believe in.

Roger: Of course; they will go on for the next five thousand years, whether it’s me or somebody else. So it’s not even worth talking about actually after a while.

Manik: Ok. But I would request you to—

Roger: Yeah, it’s a good question, I’m not saying… It’s a good question, but I’m just trying to say it’s one of those questions that… I can live with myself. No one else knows what’s going on between me and my subject, and what I take isn’t necessarily objectification of what was there. It’s a transformation. And what I’ve— results to me aren’t negative.

Alter Ego, 2010

Alter Ego, 2010

Manik: In any case, what you mean is that it’s more of an individual call and there is no justification or definition?

Roger: The problem is, you don’t want to get too deeply involved in this. You know, we’re all guilty. As I told you, we’re all guilty of even worst acts of exploitation than digging up somebody’s grave. This is, the human species is involved in destroying the planet in every way. So… And we’re all responsible for this. That to me is an important thing to always keep in your mind.

It’s not only about humans to humans. There are other things really on this planet that I believe have the right to exist in their own way. This act of exploitation, it’s what I said in the book in my own writing. To me this is a very— it’s a serious problem… It’s not a human. We’re always talking about humans to humans, but there are other things on this planet.

Manik: So does that also mean that there is no definition of photographic ethics? Because, I mean, there again it’s a very individual call…

Roger: No, of course there’s ethics. There are ethics, but unfortunately there are a lot of ethics that are hard to—they’re on grey lines. But this is the world we live in. Is it ethical that in one country somebody can justify dropping a bomb on somebody in another country? That it’s ok because we label them terrorists? You know, we can go crazy with the way we try and define the world; the world’s very confusing. And I’m not saying—of course there are rights and wrongs. But I certainly have my own belief system of what’s right and wrong. But we live in a very, very fluid world, don’t ever kid yourself.

Manik: I was just reading about you on one of the blogs, and somebody has interestingly compared your photographs to the cartoon ‘Adams family’.

Roger: (Laughs)

Bewitched, 2012

Bewitched, 2012

Manik: How does your family react to your own work, which is often contextualised as disturbing/freaky?

Roger: I have twins, a boy and a girl, who will be twenty five. They are artistic in their own way. My wife’s an artist. I guess in their own way they found it challenging; they probably found me interesting. Probably proud of me in their own way. They have their own lives and I think they respect the dedication I put into what I’ve done. They supported me in a lot of ways. Although we don’t spend a lot of time talking about the meaning of my photography like you and I are talking now. You know, I think we sort of respect each other’s needs, and as the father of the house, there’s a certain feel that… You know, the certain aspects of my father—the life he gave—I respected his work and dedication. So, I think my kids feel the same: proud, and respect the work I put in. Also, I think in their own ways I’m sure it’s rubbed off on them in many ways. My son—although he doesn’t spend that much time anymore with photography—for two or three years in a row he won an award in South Africa for the best student photographer in the country. He won that two or three years in a row and he never studied photography. He studied psychology and business, so, you know, it rubbed off in its own way. And our daughter is quite philosophical and psychological. My wife is also a novice.

Manik: Which means that each one of you respects each other, but there is no photography on the dinner table?

Roger: No, we don’t sit and debate my photography.

Manik: So my last question to you is—

Roger: Thanks. And your questions are really excellent. I’m really enjoying talking to you.

Manik: I’m glad. So, you’ve spent a lot of your time in Africa—South Africa. Last year I was trying to do my extensive research to find some photobooks by photographers in Africa. I am curious to know about the state of photography in South Africa?

Roger: Well, first of all, I have a foundation here; I try to help people with photography; I’ve been trying to do this for years. The problem is there are a lot of problems and issues. The first problem is: the market for photography and photobooks in Africa is very limited. People don’t select photography, they don’t buy photography, they don’t buy photobooks, and there are no places to sell photoboooks. So somebody who wants to become an art photographer has almost an impossible time trying to survive. That’s the first issue. The second is the printing—the camera process. Although it’s a lot cheaper than it used to be, it’s still an expense that most people can’t pay for. The third thing is, the market for all this stuff is in Europe and the United States, maybe a little bit in places like Japan, but mostly in Western Europe and the United States. For somebody who’s a student, or trying to raise a family, it’s very difficult to go back and forth, to leave people, to get the work shown, to continue their work. It’s such a competitive business, you know—that is the problem: the market isn’t here. Most people have a battle of survival, and it doesn’t mean they’re not talented people. What it means is that people can’t continue taking pictures after they leave university, leave school. They gradually give up because they can’t survive off of it; that’s the problem. On the other hand, more people are taking pictures in Africa because of the digitalisation of photography. So people are doing this all the time. The problem is, is getting the pictures out—to get people to try and look at them to try to sell them. I’m sure it’s difficult in India, too

Manik: You’re saying the economy of photography—

Roger: You talk about the whole world, maybe there’s just ten in the whole world that are really making a lot of money out of selling off photography. Out of three or four billion people taking pictures, maybe just ten that are making a really good living out of it. There’s not more than ten—name ten people in the world that make really good money from photography—maybe making two or three million dollars a year out of it. I could probably name ten people if you want.

Manik: There are a lot of them, by the way, just depending upon what they are doing.

Roger: I’m talking about art photographers—you won’t come up with more than ten. I’m talking about living photographers. I’m talking about money—making a really significant amount of money. Think about it: tell me if you can come up with more than ten.

I will be just curious to see whether you— There’s people like Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall, I don’t know, a few others that are really making it into an art. But they’re more seen as contemporary artists than photographers

Manik: But you know, I mean, even if they’re making money, is that being re-invested for photography, in supporting photography?

Roger: I have always said, ‘If Picasso lived in most countries in Africa, he would have starved to death’.

That would be my conclusion. If Picasso lived in South Africa, if Picasso lived in the Congo, or in Ethiopia he would have starved to death.

Manik: I really, really appreciate your time

Roger: And I appreciate yours.

Manik: Perfect. Thank you

Roger: Thank you. Take care. Bye

Photography Interviewed by Manik Katyal

Research by Megan Blackwell